A Perfect Storm

A Perfect Storm: Factors Contributing to the Latin American and Caribbean Region’s Particular Vulnerability to Novel and (Re)emergent Disease

Introduction

This backgrounder provides an overview of various features of the Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) region that make it especially vulnerable to health emergencies. It examines the multilayered diversity of the region, its endemic and (re)emergent diseases, and regional inequality with a focus on healthcare. It further considers the ways in which economic priorities are leading to deforestation, an increasing human-wildlife interface, and biodiversity loss, all of which increase the potential for zoonotic diseases across region. Political and economic factors further complicate the development of regional or national capacities to prevent or respond to health crises. Many of these issues are at play in the increased engagement of China in the LAC region and are exacerbated by China’s growing influence there. The paper concludes that not only is LAC a hotspot for disease (as noted in various studies), but also that the conditions are in place for a “perfect storm” in the LAC region, in which novel or (re)emergent disease, especially zoonotic disease, is increasingly likely even while states in the region are facing a range of pressures that make it more difficult for them to monitor, prevent, and respond to national or regional health events. The rapid spread and devasting impact of COVID-19 in LAC, despite the fact that health authorities had considerable time to prepare before it first appeared in the region, is illustrative of very real challenges facing LAC in this context.

Latin America and the Caribbean—A Remarkably Diverse Region

The Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region is generally defined as including Central America, South America, Mexico, and the Caribbean.[1] There are some small variations in how the region is defined in practical terms by various international bodies—generally, these reflect the inclusion or exclusion of several non-sovereign Caribbean islands and French Guiana. Leaving aside the academic debates about the region as concept or cultural space rather than a geographic region, for the purposes of this backgrounder, the self-defined membership of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) will be taken as definitive.[2] Based on CELAC’s definition of the region, LAC represents a population of about 670 million people [Worldometer, n.d.], a land mass of more than 20 million km2 (approximately 7.8 million mi2, more than twice the size of the continental United States), and a gross domestic product in 2021 of almost $5.5 trillion [Macrotrends, n.d.].

In terms of its geography, LAC includes four climate zones (tropical, temperate, arid, and cold) and three physical regions (mountains and highlands, river basins and lowlands, and coastal plains); additionally, there are five altitudinal zones defined by elevation. Not surprisingly, in geographical and climatic terms the region is remarkably diverse—it contains active volcanos and multiple fault lines,[3] continental ice, the world’s longest mountain range, the biggest river, the driest desert, the largest rainforest, and substantial agricultural and mineral resources.

This physical diversity is the foundation for Latin America’s incredible biodiversity. The United Nations Energy Programme (UNEP) estimated in 2016 that approximately 60% of global terrestrial life can be found in the region [Burgess et al., 2016] and the World Wildlife Federation (WWF) noted that 10% of that biodiversity can be found within the Amazon biome alone, which includes multiple ecosystems (and the prospect of even greater, as-yet-unknown biodiversity [Hance, 2007]) spread across eight countries [WWF, n.d.]. Six countries in the LAC are megadiverse, defined as having at least 5,000 endemic plants and bordering on marine ecosystems,[4] and five were among the top 10 most biodiverse countries in 2022 as measured by the Global Biodiversity Index [Nash, 2022].[5]

It is noteworthy that the LAC region’s diversity includes microbial diversity, which is described as “extensive and … endemic for a wide array of infections” [Yeh, 2021]. Kenneth Yeh and his colleagues provided an overview of endemic viruses and diseases in the region, including dengue, malaria, Chagas, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, chikungunya, malaria, tuberculosis, various arenaviruses (including Chapare, Guanarito, Junin, Machupo, and Sabia), various flaviviruses (such as yellow fever and Zika), and various alphaviruses (including Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis, Eastern Equine Encephalitis and Mayaro) [Ibid., p. 19]. Image 1 summarizes the regional distribution of endemic vector-borne diseases in LAC.

Image 1. Vector-Borne Diseases in LAC, 2016.[6] Source: [PAHO, n.d.].Image 3. Vector-Borne Diseases in LAC, 2016.[6] Source: [PAHO, n.d.].

Regional Inequality—Focus on Healthcare

When considering the susceptibility of LAC populations to the region’s endemic and (re)emergent diseases and the potential impact that these may have across the region and beyond, there are a number of socio-economic and political factors specific to LAC that should be kept in mind.

Across the region, according to criteria used by the World Bank, most countries are considered to be upper-middle income based on gross national income (GNI) per capita (19), with a number of countries characterized as high-income (7) and a handful in the lower-middle income group (5). No country in the region falls into the low-income group.

Table 1. LAC Countries by Income Level (2023 Fiscal)

| Income Group | Country |

| High | Bahamas, Barbados, Chile, Panama, St. Kitts and Nevis, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay |

| Upper-Middle | Argentina, Belize, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Jamaica, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Surname |

| Lower-Middle |

Bolivia, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua

|

Source: WB [n.d.].

However, in its 2019 economic outlook report for LAC, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) emphasized that countries with similar per capita incomes may nevertheless have very different development profiles, noting that “national averages hide a large diversity of economic and social outcomes across subnational regions.” At the regional level, the same report described disparities among states nominally at the same level of income per capita as “glaring” [OECD, 2019]. Illustrative of the first point is the fact that, although there is considerable wealth in Latin America, significant numbers of people in the region live in extreme poverty.[7] In 2016, the executive secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) noted that Latin America is “the most unequal region of the world,” in which 71% of the region’s wealth is in the hands of just 10% of the population, and much of that is held offshore or untaxed [Bárcena, 2016]. In fact, less than 10% of total tax revenues in LAC come from personal income taxes (compared to the OECD average of 25%), while in (at least) eight countries, the top 10% income earners pay less than 5% of their income in personal taxes [Segal, 2022, pp. 1088–9]. By 2020, inequality in the region had been reduced to a degree, with 54% of the region’s wealth being held by the richest 10%, and declines in inequality were observed in several LAC countries [World Inequality Database, 2020]. Yet, despite these advances, only a year ago Paul Segal was still able to describe inequality as “one of the most striking features of most Latin American societies” [2022].[8]

Infectious Disease on the Rise

Writing during the 2016 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa, Marcos Espinal and his colleagues considered the possibility that the virus could spread to Latin America. While noting that such a possibility was generally seen to be low, they stressed that “the region has all the ingredients to have imported cases of Ebola virus disease and of any other emerging and reemerging infectious diseases, with potential of further spread” [2016, p. 279]. In this context, they pointed to a growing number of events of potential international public concern, including 93 such events in 2014, of which more than half were substantiated and affected 27 countries and territories [Ibid.]. Yeh and his colleagues cited this as evidence of LAC being at “particularly high risk of emerging and re-emerging infection diseases” [Yeh, p. 19].

The Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), in its most recent Plan of Action on Entomology and Vector Control (2018–2023), warned that there have been repeated dengue epidemics over the past 30 years, and that cases have been on the rise since 2000 and are spreading to new geographic areas. Chikungunya and Zika, having appeared in the region relatively recently (2013–14 and 2015–16, respectively), quickly became endemic. Alfonso Rodriquez-Morales and his colleagues referenced a number of other notable outbreaks since 2019, including of a “staggering” number of measles cases in 2019–20 across 14 countries (but mostly in Brazil), reported increases (by two and three times) of dengue in Bolivia, Honduras, Mexico, and Paraguay, and diphtheria and vector-borne diseases spreading from Venezuela [2020].[17]

Even in 1996, it seemed that the incidence of infectious diseases in LAC was increasing. David Brandling-Bennett and Francisco Pinheiro addressed this issue specifically, asking whether the apparent increase was real or was rather the result of better reporting. Significantly, they determined that the answer is “both.” In accounting for the reemergence of diseases such as dengue, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and cholera, Brandling-Bennet and Pinheiro pointed to a number of factors that are closely related to the issues already identified in this backgrounder. These factors include low levels of investment in public health, urbanization, invasion and deforestation of the forests due to population or commercial pressure, and climate change [1996]. The impact of low investment levels in public health and the resulting vulnerability of populations to disease in this context is already established. Perhaps less obvious are the intersections between these other factors and increases in infectious diseases.

The Increasing—and Increasingly Pathogenic—Human-Wildlife Interface

Reframed as an expansion of the animal-human interface, the connection of urbanization, deforestation, and climate change to increasing infectious disease becomes very clear. In 2008, Kate Jones and her colleagues [2008] asked the same question that Brandling-Bennett and Pinhiero had asked a decade earlier—can the increasing incidence of emerging infectious diseases be explained by increased reporting? Based on their analysis, they concluded that, even controlling for reporting, emerging infectious disease events are clearly increasing over time. And, as did Brandling-Bennett and Pinhiero, Jones et al. concluded that this is “significantly correlated with socio-economic, environmental and ecological factors.” Importantly, based on analysis of these factors, their results also provided a way to identify regions they described as “emerging disease ‘hotspots.’ ” As they noted, most emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic in nature (60.3%), with the majority of those (71.8%) originating in wildlife; they also hypothesized that this is highly correlated with wildlife biodiversity. Among their conclusions was that parts of low-latitude Latin America can be considered “hotspots” for emerging infectious diseases originating from wildlife, as well as vector-borne pathogens. Among their recommendations, largely focused on health monitoring in disease hotspots, was that efforts should be made to reduce human activity in areas characterized by high biodiversity in order to reduce the chances of zoonotic disease emergence. Fifteen years later, there is a significant scientific literature linking the emergence of infectious diseases to the human-animal interface, and it goes without saying that in the post-COVID-19 world, the implications of increasing contact between people and wildlife have become especially stark.

A number of the factors identified by Brandling-Bennett and Pinhiero in 1996 as connected to increasing emergent disease events—urbanization, the invasion of the forests due to population or commercial pressure and climate change—are so precisely because they are driving increased human-animal, and especially wildlife, interaction. They fuel, and are fueled by, changing land use patterns, demographic growth and rapid environmental changes (as opposed to long-term climate change) in complex, interconnected, and sometimes unpredictable ways.

Perhaps most significant driver of these trends in the LAC region is the deforestation of the Amazon. Joel Henrique Ellwanger and his co-authors undertook a review of the far-reaching and sometimes unanticipated impacts that Amazon deforestation has on infectious diseases and public health. Their analysis began by noting that there is a “robust body of evidence” connecting deforestation of the Amazon with climate change and, further, that “the link between ‘environmental imbalances’ and ‘emerging infectious diseases’ is already well established in the literature” [2020, pp. 2–3]. Moving beyond the impacts specific to climate change, they focused on the ways in which a wide range of trends associated with deforestation in the region—agricultural intensification and land use change, mining, water contamination and flooding, urbanization and de-urbanization, hydroelectric dams and irrigation systems, transportation infrastructure, human migration, hunting and consumption of bushmeat, and prostitution—increase human-wildlife interaction, impact vector dynamics, and promote the circulation of pathogens.

Like Jones et al., who determined a correlation between zoonotic disease and biodiversity and recommended reduced human activity in biodiverse areas, Ellwanger et al. highlighted the fact that biodiverse areas contain diverse pathogens, and that “preserving these environments and their rich biodiversity is, to a certain extent, a way to prevent emerging infectious diseases…disturbances in highly biodiverse ecosystems facilitate the emergence and spread of new human infections” [p. 14]. However, they also noted that the loss of biodiversity in and of itself can impact the emergence of infectious disease. Citing the work carried out in previous studies, they warned that “the loss of animal and plant biodiversity diminishes and even extinguishes ecological niches occupied by predators, disease vectors, and pathogens. On the other hand, biodiversity loss creates new niches that may be occupied by alternative reservoir species, vectors, hosts, and pathogens” [Ibid.].

It is thus a cause for considerable concern that, as is frequently reported, deforestation has already had a significant impact on the biodiversity of the Amazon biome. A 2022 WWF report found that 26% of the Amazon is in a state of “advanced disturbance” and that amphibian, bird, mammal, fish, and reptile populations in the region have declined an average of 69% over the last 50 years [Pelcastre, 2022]. Not only is deforestation of the Amazon increasing the intersection of human-wildlife habitats, but it is also making that intersection potentially more pathogenic.

Beyond the Amazon Biome

As the country with the largest portion of the Amazon within its borders, Brazil is especially impacted by deforestation but the other countries in the Amazon basin (Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, and Suriname) are also experiencing biodiversity loss. Beyond the Amazon, the pattern is being reproduced across the region, and the WWF report identified other areas of particular concern in LAC—in the Atlantic Forest (which includes parts of Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay), the northern Andes as far as Panama and Costa Rica, and the Maya Biosphere reserve in Guatemala.

Land conversion in support of economic activities is the key driver of deforestation and human encroachment on wildlife habitats. Many countries in LAC are dependent on resource extraction (including mining[18] and petroleum) and agriculture. Several LAC countries are significant producers of meat and poultry—Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay are globally important beef producers, while Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, and Colombia are among the world’s top chicken producers.[19] In addition to meat production, export commodities such as guano, sugar, soybeans, coffee, tobacco, petroleum, iron ore, and copper are important contributors to national budgets. Increasing international demand for commodities has been a driving factor in the conversion of forest into agricultural land. Viviana Zalles and her co-authors found that agricultural production in South America increased significantly between 1985–2018 and suggested that “as increases in agricultural commodity production are linked to commodity land uses, no region on Earth is likely to have experienced the scale of land conversion for the sake of agricultural commodity production that South America has” [2021]. Specifically, they determined that since 1985, the area of land under natural tree cover had decreased by 16%, whereas there had been substantial increases in land being used for pasture (23%), cropland (160%), and plantations (288%). With reference the region as a whole, a 2019 United Nations report similarly noted an increase between 2000–2016 in the net conversion of forests to croplands and other uses—during this period, there was a 70% increase in croplands and a 55% reduction in forests [UN Convention to Combat Desertification, 2019, p. 18].[20]

The involvement of organized crime in activities contributing to deforestation and increased interaction between humans and wildlife cannot be overlooked. Jennifer Devine noted that South and Central American drug trafficking organizations are “the vanguard of deforestation” [Devine, 2021] illegally logging and raising cattle as a means to launder money. The WWF report similarly linked deforestation in Colombia’s Amazon to the activities of the National Liberation Army and the Clan de Golfo, both linked to illegal logging and mining, while in Guatemala nacrotraffickers clear forest to make way for landing strips. Also of grave concern is the illegal traffic in wildlife across the region; Sharon Guynup warned that wildlife trafficking has become the fourth largest criminal activity globally and is “now the paramount threat” to the animals in the region, noting that LAC has “experienced catastrophic wildlife declines” in the past 40 years [2022].

Taken together, the increasing human-wildlife interface, the loss of biodiversity, and the concomitant risk of emergent infectious disease are a clear cause for concern. Many governments in the region have already sounded the alarm on deforestation, and there are projects underway to try to slow or reverse it, often with the support of organizations like the World Bank. Several countries have managed to reduce agricultural areas and increase forest areas, to keep agricultural and forest land stable, or—as in the case of Chile—to increase both agricultural and forest areas [UN Convention to Combat Desertification, 2019, p. 19]. However, sustained government action and coordination across the region is often difficult to muster given that many LAC countries experience economic and political instability, both of which compromise the ability of states to respond to these challenges and the health events that may result.

Economic and Political Instability

The LAC region has a complicated history in which war, authoritarianism, social unrest, and economic and political dependence have figured prominently. Even after the move toward democracy across most of the region in the 1980s, LAC has not been able to escape the lingering impact of these features of its past. Today, the region continues to experience mutually reinforcing economic and political instability in a context of considerable inequality, which not only drives the processes described above, but also complicates the ability of states to change course.

On the economic side, as already noted, a key driver of deforestation and land conversion is the heavy dependence of many LAC countries on trade in commodities. Given this external orientation, LAC economies are thus disproportionately tethered to the global market—healthy international demand for the region’s goods is vital. Global recessions are “always bad news for commodities” as they result in lowered demand for commodities, a situation that is “never good for a region that has an economy that can be considered ‘old,’ as is the case of Latin America” [Alvarez, 2023]. Declining or fluctuating revenues from trade puts further strain on economies that are already struggling to manage significant economic challenges. In the 1990s, the region was hard-hit by a series of external shocks, including the Mexican, Argentinean, Russian, Brazilian, and Asian financial crises; it was hit again during the 2008 financial crisis. At present, there are signs that a post-covid global recession is on the near horizon.

In addition to, or perhaps because of, the impact that this has on the ability of states to allocate resources for social spending on things like infrastructure, healthcare, education, and poverty reduction, there is a direct line leading from economic challenges such as these to political instability. Monica de Bolle [2022] described how popular dissatisfaction with governments’ economic performance has led to a “hollowing out” of the political center and has driven voters in states like Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico to elect leaders from the political extremes, who may or may not be able to enact appropriate policy responses to the economic challenges they face. As de Bolle noted, LAC societies are highly polarized, and “the region’s governments have lurched back and forth from right to left during election cycles, with each new regime undoing what came before it, including sensible policies and reforms in many cases.” It is this last point that de Bolle particularly emphasized—the absence of policy continuity is a matter of concern because, without it, long-term sustainable growth becomes unlikely.

Undoubtedly, there are many other reasons to be concerned about economic and political instability, including regional geopolitical considerations and issues related to inequality and social justice. The rise of extremism seems unlikely to remedy the inequality that characterizes the region, as previously discussed, and that too may increasingly become a source of political instability. However in the context of this backgrounder, the key point is that, while governments in the region are very much aware of the challenges they face with respect to their vulnerability to disease and disease events and the risks that come with an increased human-wildlife intersection, and moreover may have developed pandemic preparedness strategies to respond to these issues, they may find it difficult to carry out a program of action over the long term. While there are other factors that may compromise the ability to states to act—notably corruption and organized crime—vulnerable governments may be focused on serving short-term interests rather than committing resources to long-term plans that could be reversed at the next election.

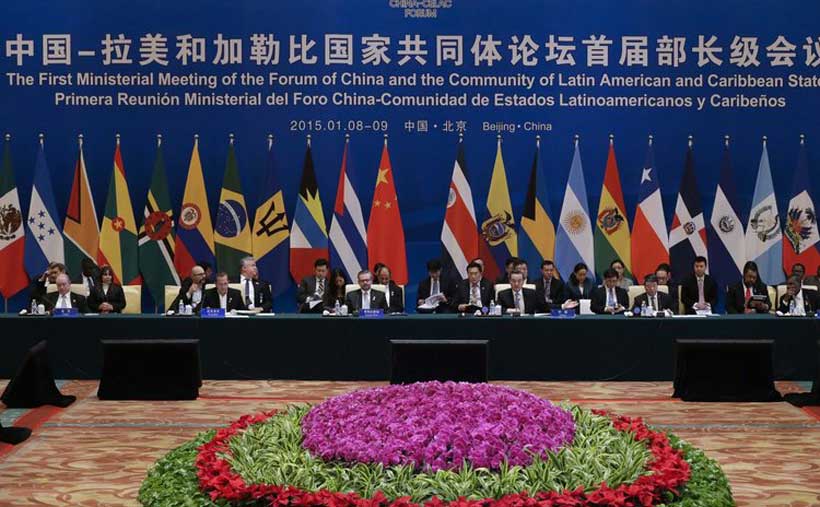

China’s Regional Influence

The interconnectedness of these many issues as they relate to endemic and (re)emergent diseases in LAC, and its particular vulnerability to them, can be illustrated by considering the growing influence of China in the LAC region. In the space of about 20 years, trade between China and LAC increased 26-fold, with China becoming the region’s second largest trading partner (after the U.S.), and the top trading partner for South America. Further, China has signed free trade agreements with a number of LAC countries. China directs considerable official development assistance (ODA) to the region, and its commercial and policy banks are major lenders to many LAC countries—Diana Roy [2022] estimated that in 2020 Chinese ODA amounted to $17 billion (mostly in South America), and that $137 billion was loaned between 2005 and 2020.

China has been actively pursuing its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—a multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure financing program—in LAC since 2017, attracted by the region’s natural resources and agricultural products, and also by the potential for LAC to become an export market for Chinese goods.[21] Latin American countries have been very receptive, and as of December 2021, 20 countries in LAC were official participants in the BRI. Not surprisingly, as Werner Raza and Hannes Grohs observed [2022], many LAC countries view “enhanced economic and political relations with China as strategically important…the relationship offer[s] the option of increasing export revenues, technology transfer and an additional source of external finance…[and] less economic dependence on traditional export markets in the US and Europe.” Alvarez [2023] underscored the significance of trade with China, noting that in the context of an expected global slowdown in 2023, “practically all analyses of what may happen to the Chilean economy…place the Chinese factor on the table: if the restrictions on mobility caused by the coronavirus are lifted, China will demand copper, and this will benefit Chile. If the opposite happens, the South American country will suffer.” “The same,” he continued, “can be replicated when thinking about soybeans on the Argentine side and there would be an example for every country in the region.”

However appealing the influx of Chinese investment and trade may be for countries in the region, there is cause for concern at the same time. As have others, Julio Armando Guzmán noted that, post-COVID, Latin America is heading into a period of low growth as commodity prices fall, interest rates climb, and global demand stalls. In that context, he suggested that “Chinese investment…will be hard to resist,” while also warning that the “money comes with strings attached.” LAC’s economic vulnerability and China’s ability to mitigate the impacts of declining GDPs across the region means that LAC governments will have “less political leverage …to resist keeping the economy afloat at any costs” [2023].

There are many economic and political costs that could come with the region’s reliance on Chinese investment and trade. Against the backdrop of political instability and economic vulnerability, many observers have warned that China’s growing influence in the region is a cause for concern with regard to deforestation and biodiversity loss.

Hongbo Yang and his colleagues undertook a global assessment of the risks posed by China’s overseas development financing to biodiversity and Indigenous lands, tracking lending by the two leading Chinese policy banks from 2008 to 2019. A key finding of their study is that 63% of China’s foreign direct investment loans (FDI) involve project sites that overlap with critical habitats, designated protect areas, or Indigenous lands—the Amazon basin is identified by the authors as one of the global hotspots in which there are risks both to biodiversity and to Indigenous lands [2021, p. 1521]. They also found that, compared to projects financed by the World Bank, those financed by China’s policy banks “present greater risks” to biodiversity and Indigenous lands [Ibid., p. 1523]. However, Yan and his co-authors did not suggest that there is anything inherently problematic about Chinese investment, and that it is possible that these high-risk projects were approved because they serve an important social purpose (such as road improvements in remote areas) or because appropriate risk-mediation strategies had been developed.

Divya Narain adopted a less agnostic position on the question of Chinese investment, noting that two of the biggest Chinese development banks do not have any biodiversity safeguards, that only one out of 35 Chinese investors in the BRI has any biodiversity safeguards, and that Chinese regulators do not specify any binding biodiversity impact mitigation requirements [2022, p. iii]. As she pointed out, this means that the responsibility for developing and enforcing biodiversity safeguards falls on the recipient country, a task that, for reasons outlined above, LAC states be reluctant or unable to carry out.[22] Ciara Nugent and Charlie Campell [2021] offered a few examples of projects that highlight the problem, including the cancellation of an oil refinery project in Costa Rica after local officials uncovered a conflict of interest in the performance of the environmental impact studies and a disastrous dam project in Ecuador that was facilitated by widespread bribery. Maxwell Radwin [2023] provided an overview of a report to the UN that examined 14 projects in nine LAC countries, in which “corporate abuses” took place in “fragile ecosystems” and resulted in “significant environmental damage.” These projects included dams, oil fields, trains, and animal processing plants.

In addition to the direct impact of Chinese infrastructure projects in the region, there has been an indirect, and perhaps even more significant, impact on biodiversity in LAC related to the increased Chinese presence. As the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission stated unequivocally [2018] that China is the largest market for trafficked wildlife products. In this connection, Guynup suggested that the influx of Chinese companies and workers into LAC has created “a pipeline for wildlife trade,” noting that the deforestation and incursions created by infrastructure projects and the extraction of natural resources opens space for poachers to operate with ease [2023].[23] This cannot be separated from organized crime; according to Interpol, wildlife trafficking and related crimes (money laundering, corruption, fraud) is valued at $20 billion per year [Interpol, n.d.].[24] In light of the involvement of organized crime, many LAC states have elevated wildlife trafficking to the level of national security; however, as Guynup detailed, citing a UN investigation, the ability of many LAC states to combat the issue is undermined by widespread corruption involving park rangers, police, military personnel, customs agents, and high-level officials. The involvement of organized crime, in particular, makes intervention efforts very dangerous—a report by Global Witness found that 75% of the 200 environmentalists killed globally in 2021 were in Latin America. Significantly, local authorities, along with businesses and “other non-state actors” were implicated, but perpetrators are rarely brought to justice [Hines, 2022].

The LAC Region – The Perfect Storm

Taking into consideration all of these factors, it is clear that LAC is more than a hotspot for disease; to the extent that the states of the region are limited in their abilities to manage the challenge—and indeed, to the extent that their economic and political agendas are exacerbating the problem—it is clear that the conditions in the region are ripe for the “perfect storm.” The devasting impact and rapid spread of COVID-19 in LAC [Gamba, et al., 2022],[25] despite the fact that health authorities had considerable time to prepare before it first appeared in the region (the first case in the region was reported on 26 February 2020), is illustrative of very real challenges in this context.

Yeh et al., in their review of global health risks in Latin America, noted that, with respect the spread of COVID-19 throughout the region, “the combination of inconsistent health care infrastructure, fragile economies, and complex political and economic landscapes has enabled the intense spread of COVID-19 to even the most remote areas of Latin America including indigenous populations along the Amazon that can only be reached by boat” [2021]. Fernando Ruiz-Gómez and Julián Fernández-Niño [2022] explained that the impact of COVID-19 in rural and remote areas was unexpected because populations are dispersed and young but that regional disparities in health care, a weakened health authority, and historical social inequalities instead made these areas especially vulnerable. Alvaro Schwalb and his colleagues [2022] also determined that in addition to general pandemic unpreparedness, “fragile healthcare systems, forthright inequalities, and poor governmental support facilitated the spread of the virus throughout the region.” They further noted that, despite the late arrival of COVID-19 to the region and the time to learn from strategies developed elsewhere, the impact of the virus was “catastrophic.”

To this point, William Savedoff and his colleagues [2022] pointed to the fact that LAC countries tried to take advantage of this delay in the arrival of COVID-19 by implementing early measures such as lock-downs, limits on travel, and closures of schools, and that by 1 April most countries in the region had implemented strict containment policies. However, they noted that the application of these measures varied widely across the region, as did “internal coordination, leadership commitment, enforcement, and public coordination.” They also noted, as have other observers, that the fact of the large informal economy, within which people work or do not get paid, across the region cannot be overlooked as a key factor affecting the transmission of COVID-19.

These are just some of the ways that the factors discussed in this backgrounder intersected to make the region especially, and variably, susceptible to the spread of COVID-19 across LAC, and it is reasonable to expect that, even with substantial health care investments, the broader socio-economic and political issues will continue to impact LAC countries’ ability to effectively respond to future health crises.

Conclusion

The issues and complications outlined in this backgrounder can only be addressed through concerted action by states across the LAC region, and even in that case they cannot be isolated from a whole array of cross-cutting global issues. None of them will be resolved except in the long term. And yet, the threat posed by endemic and (re)emergent disease in the region warrants a response on a much shorter timeline.

In the short to medium term, especially when multiple factors complicate the ability to respond to endemic or (re)emergent or disease, it is vital to enhance resources to detect and monitor such diseases as quickly as possible. Laboratories are a key resource in this context and are a vital element of pandemic preparedness. Adequate biosafety and biosecurity practices carried out by trained professionals in the context of appropriately designed laboratories form an indispensable element of a “first line of defense,” particularly when laboratories are required by circumstance to be flexible with respect to the pathogens that they may be required to manage. Importantly, the strengthening of national or regional laboratory capacity is a relatively straight-forward undertaking; while significant investments may be necessary to expand and maintain laboratory infrastructure, health system gap assessments such as those facilitated by the WHO’s joint external evaluation (JEE) process may help LAC states to develop cost-effective and targeted strategies to improve their capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to health events. Improved laboratory capacity in this context is only one piece of a much larger and complex health security puzzle in the region; however, it is a critically important piece, and one that could buy time while other elements are being worked out over the longer term. A number of states in the LAC region have recently invested, or are currently planning to invest, resources to strengthen their laboratory capacity, including Mexico, Colombia, Bolivia, Brazil, Panama, and Peru.

Notes

[1] The region is often referred to simply as “Latin America,” a term that is assumed to include the Caribbean.

[2] These are: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Panama, Dominican Republic, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, St. Lucia, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Venezuela. See CELAC [n.d.].

[3] The United States Geological Service (USGS) describes South America as “one of the most earthquake-prone regions in the world” [La Point, 2018] while Moody’s [n.d.] notes that the LAC region spans “different complex tectonic environments.”

[4] Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela.

[5] In order, Brazil (1), Colombia (3), Mexico (5), Peru (7) and Ecuador (9).

[6] Compiled by PAHO based on data collected between 2000–2016.

[7] The World Bank estimates that approximately 11% of people in 18 LAC countries are living in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than $1.90 per day [Alvarez, 2022].

[8] It goes without saying that economic inequality cannot be understood apart from the social, cultural, and political-legal institutions that support and reproduce it. This backgrounder does not address the broader context of inequality in the region other than noting that the economic inequality created/maintained by a taxation system that favors the 10% is clearly as much of a political issue as an economic one.

[9] These indicators (and their sub-indicators) were individually ranked to determine an overall “health system score”: health capacity in clinics, hospitals and community care centers, facilities capacity, supply chain for health system and healthcare workers, medical countermeasures and personnel deployment, healthcare access, communications with healthcare workers during a public health emergency, infection control practices, and capacity to test and approve new medical countermeasures. The GHS Index, including the report, the data model, and the methodology report, are available at: https://www.ghsindex.org/report-model/.

[10] Dominica and St Kitts and Nevis.

[11] Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, St Lucia, and Venezuela.

[12] St Vincent and the Grenadines and Suriname.

[13] Costa Rica, El Salvador, Paraguay, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uruguay.

[14] Brazil and Nicaragua.

[15] Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, and Panama.

[16] Argentina and Peru.

[17] Writing at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors were already anticipating that, following the identification of the first case in Brazil in February 2020, a “significant expansion in the region would be possible.”

[18] PAHO described the considerable progress that has been made toward the elimination of malaria in the Americas but also noted that the expansion of gold mining in the absence of environmental or vector control measures has led to outbreaks in Guyana, some countries in Central America, and Venezuela [2018, p. 3].

[19] In addition to contributing to biodiversity loss through conversion of land to pasture, the growth of industrialized meat production brings with it increased risks of zoonotic pathogens among animals kept in unnatural conditions and also amplifies the human-animal interface.

[20] The connection between this conversion to agricultural land use and biodiversity loss can be traced in sometimes unexpected ways. The Atlantic Forest, located on the Atlantic coast of Brazil and including parts of Paraguay and Argentina, remains one of the most biodiverse regions in the world despite the massive impact of human activity—logging, pasture, and agriculture (88% of the forest has been converted to date). In addition to the direct loss of biodiversity that has resulted, the increased human-wildlife interface creates further challenges. Just one of these is the threat posed by the expansion of wild pigs across South America, and in the Atlantic Forest specifically. Clarissa Alves de Rosa noted that wild pigs—which can have significant environmental impacts related to soil damage, destruction of water springs, and feeding habits—are thriving at the “perfect” environment that exists at intersection of farm and forest. As she noted, “they have the perfect environment—there are forest fragments where they can take shelter and agricultural crops where they can feed” [cited in Araujo Prado dos Anjos, 2023].

[21] There are, of course, political motivations for the expansion of the BRI to Latin America, most notably the drive to isolate Taiwan.

[22] Narain found that only 60% of the countries with BRI hydropower projects also had biodiversity impact mitigation policies [Ibid., p. iv.].

[23] She also noted the increase in large-scale hunting for bushmeat fueled by Chinese workers; Yeh et al. [2021] discussed the direct health risks associated with increasing demand/consumption of bushmeat.

[24] Nor can it be separated from big business. In October 2023, the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) UK reported that it had found evidence that 72 Chinese companies—including three large, publicly listed Chinese pharmaceutical groups—are using body parts of animals for which international trade is prohibited by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The report noted that, with respect to leopards (which are found in South and Central America), the fact that they are not commonly bred in captivity, that their numbers in China are small, and that they are protected by the CITES prohibition on their trade, “it is unclear how procurement for these products can be met through legal supplies.” Major companies and financial institutions, including BlackRock, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, the Royal Bank of Canada, and HSBC are among the investors in these Chinese pharma companies, despite public declarations in support of for biodiversity conservation [EIA, 2023].

[25] LAC has been characterized as one of the epicenters of the pandemic, accounting for 15% of all cases globally, and a staggering 28% of all deaths, while making up only 8.4% of the world’s population [Gamba et al., 2022].

References

Alvarez J. P. (2022) Más del 25% de la población de América Latina es pobre: en que regiones es mayor. Bloomberg Línea, 4 October. Available at: https://www.bloomberglinea.com/english/number-of-latin-americans-living-in-poverty-expected-to-surpass-one-third-of-total/ (accessed 28 March 2023) (in Spanish).

Alvarez J. P. (2023) Five Economic Challenges Facing Latin America in 2023. Bloomberg Línea, 6 January. Available at: https://www.bloomberglinea.com/english/5-economic-challenges-facing-latin-america-in-2023/?outputType=amp (accessed 28 March 2023).

Araujo Prado dos Anjos V. A. (2023) Wild Pigs Threaten Biodiversity Hotspots Across South America, Studies Shows. Mongabay, 12 June. Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2023/06/wild-pigs-threaten-biodiversity-hotspots-across-south-america-study-shows/(accessed 23 October, 2023).

Brandling-Bennett D., Pinheiro F. (1996) Infectious Diseases in Latin America and the Caribbean: Are They Really Emerging and Increasing? Emerging Infection Diseases, vol. 2, no 1. Available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/2/1/96-0109_article (accessed 28 March 2023).

Bárcena A. (2016) Latin America is the World’s Most Unequal Region: Here’s How to Fix It. Available at: https://www.cepal.org/en/articulos/2016-america-latina-caribe-es-la-region-mas-desigual-mundo-como-solucionarlo (accessed 11 May 2023).

Burgess N. D., Allison, H. Shennan-Farpon Y., Shepherd E. (2016) The State of Biodiversity in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Mid-Term Review of Progress Towards the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. UNEP-WCMC. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/gbo/gbo4/outlook-grulac-en.pdf (accessed 11 May 2023).

Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) (n.d.) Available at: https://celacinternational.org (accessed 1 April 2023).

De Bolle M. (2022) Latin America’s Unstable Politics Dim Hopes for Economic Growth. 29 June. Peterson Institute for International Economics. Available at: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/latin-americas-unstable-politics-dim-hopes-economic-growth (accessed 1 April 2023).

Devine J. (2021) Organized Crime Is a Top Driver of Global Deforestation—Along With Beef, Soy, Palm Oil and Wood Products. The Conversation, 15 November. Available at: https://theconversation.com/organized-crime-is-a-top-driver-of-global-deforestation-along-with-beef-soy-palm-oil-and-wood-products-170906 (accessed 6 April 2023).

Ellwanger J. H., Kulmann-Leal B., Kaminski V. L., Valverde-Villegas J. M., da Veiga A. B. G., Spilki F. R., Fearnside P. M., Caesar L., Giatti L. L., Wallau G. L., Almedia S. E. M., Borba M. R., da Hora V. P., Chies J. A, B. (2020) Beyond Diversity Loss and Climate Change: Impacts of Amazon Deforestation on Infectious Diseases and Public Health. Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences, vol. 92, no 1. Available at: http://www.doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202020191375

Environmental Investigation Agency (2023) Investigating in Extinction: How the Global Financial Sector Profits From Traditional Medicine Firms Using Threatened Species. Available at: https://eia-international.org/wp-content/uploads/EIA-Investing-in-Extinction-FINAL.pdf (accessed 23 October 2023).

Espinal M., Aldighieri S., St. John R., Becerra-Posada F., Etienne C. (2016) International Health Regulation, Ebola, and Emerging Infection Diseases in Latin America and the Caribbean. American Journal of Public Health, vol. 106, no 1, pp. 279–82. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2015.302969

Gamba M. R., LeBlanc T. T., Vázquez D., dos Santas E. P., Franco O. H. (2022) Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capacity in Latin America and the Caribbean. American Journal of Public Health. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306815 (accessed 11 May 2023).

Global Health Security Index (GHS) (2021) Report and Data. Available at: https://www.ghsindex.org/report-model/ (accessed 11 May 2023).

Guynup S. (2023) The Growing Latin America-to-Asia Wildlife Crisis. Revista Harvard Review of Latin America, 3 February. Available at: https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/the-growing-latin-america-to-asia-wildlife-crisis-can-targeted-action-stop-illegal-trade-in-time-to-prevent-widespread-losses/ (accessed 6 April 2023).

Guzmán J. A. (2023) China’s Latin American Power Plan. Foreign Affairs, 16 January. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/central-america-caribbean/chinas-latin-american-power-play?check_logged_in=1&utm_medium=promo_email&utm_source=lo_flows&utm_campaign=registered_user_welcome&utm_term=email_1&utm_content=20230407(accessed 13 April 2023).

Hance J. (2007) Amazon Plant Diversity Still a Mystery. Mongabay, 21 October. Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2007/10/amazon-plant-diversity-still-a-mystery/ (accessed 23 March 2023).

Hines A. (2022) Decade of Defiance. Global Witness, 29 September. Available at: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/decade-defiance/ (accessed 21 April 2023).

Interpol (n.d.) Wildlife Crime. Available at: https://www.interpol.int/en/Crimes/Environmental-crime/Wildlife-crime (accessed 21 April 2023).

Jones K., Patel N. G., Levy M. A., Storeygard A., Balk D., Gittleman J. L., Daszak P. (2008) Global Trends in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Nature, vol. 451, pp. 990–3. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature06536 (accessed 29 March 2023).

Macrotrends (n.d.) Latin America & Caribbean GDP 1960–2023. Available at: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/LCN/latin-america-caribbean-/gdp-gross-domestic-product (accessed 11 May 2023).

Moody’s (n.d.) South America, Central America, and Caribbean Earthquake Risk. Available at: https://www.rms.com/models/earthquake/latin-america-and-caribbean (accessed 11 May 2023).

Nash M. (2022) The 201 Most (& Least) Biodiverse Countries. The Swiftest. Available at: https://theswiftest.com/biodiversity-index/(accessed 23 October 2023).

Narain D. (2022) Biodiversity Risks and Safeguards of Global Infrastructure Finance: The Case of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Queenland. Available at: https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:63970a4 (accessed 13 April 2023).

Nugent C., Campell C. (2021) The U.S. and China Are Battling for Influence in Latin America, and the Pandemic Has Raised the Stakes. Time, 4 February. Available at: https://time.com/5936037/us-china-latin-america-influence/ (accessed 13 April 2023).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (n.d.) Health at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/e22c8d68-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/e22c8d68-en (accessed 11 May 2023).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2019) Latin American Economic Outlook: Development in Transition. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/a46067bf-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/a46067bf-en (accessed 11 May 2023).

Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) (n.d.) Vector-Borne Diseases in LAC. Available at: https://ais.paho.org/phip/viz/cha_cd_vectorborndiseases.asp. Accessed 15 April 2023).

Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) (2018) Plan of Action on Entomology and Vector Control, 2018–2023. CD56/11. Available at: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/cd5611-plan-action-entomology-and-vector-control-2018-2023 (accessed 11 May 2023).

Pelcastre J. (2022) Latin America’s Biodiversity Rapidly Plummeting. Diálogo Americas, 5 December. Available at: https://dialogo-americas.com/articles/latin-americas-biodiversity-rapidly-plummeting/#.ZCReli2cbFx (accessed 6 April 2023).

Physiography, Geography and Climate of Latin America (“Lecture 3”) (n.d.) Available at: https://personal.utdallas.edu/~pujana/latin/PDFS/Lecture%203%20-Physiography,%20Geography%20and%20Climate%20of%20L.A.pdf (accessed 11 May 2023).

La Point D. (2018) New USGA Report on Seismic Hazard, Risk, and Design for South America. United States Geological Service (USGS), 14 March. Available at: https://www.usgs.gov/news/featured-story/usgs-authors-new-report-seismic-hazard-risk-and-design-south-america (accessed 11 May 2023).

Radwin M. (2023) Chinese Investment Continues to Hurt Latin American Ecosystems, Report Says. Mongabay, 28 February. Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2023/02/chinese-investment-plagues-latin-american-ecosystems-report-says/ (accessed 13 April 2023).

Raza W., Grohs H. (2022) Trade Aspects of China’s Presence in Latin America and the Caribbean. European Parliament Briefing PE 702.572. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/702572/EXPO_BRI(2022)702572_EN.pdf (accessed 13 April 2023).

Rodriguez-Morales A. J., Gallego V., Escalera-Antezana J. P. , Méndez C. A., Zambrano L. I., Franco-Paredes C., Suárez J. A., Rodriguez-Enciso H. D., Balbin-Ramon G. J., Savio-Larriera E., Risquez A., Cimerman S. (2020) COVID-19 in Latin America: The Implications of the First Confirmed Case in Brazil.

Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, vol. 35, 101613. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101613

Roy D. (2022) China’s Growing Influence in Latin America. Council on Foreign Relations Backgrounder, 12 April 2022. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-influence-latin-america-argentina-brazil-venezuela-security-energy-bri (accessed 13 April 2023).

Ruano A. L., Rodríguez D., Rossi P. B., Maceira D. (2021) Understanding Inequities in Health and Health Systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Thematic Series. International Journal for Equity in Health, vol. 20. Available at: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-021-01426-1 (accessed 11 May 2023).

Ruiz-Gómez F., Fernández-Niño J. (2022) The Fight Against COVID-19: A Perspective From Latin America and the Caribbean.American Journal of Public Health. Available at: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306811 (accessed 11 May 2023).

Savedov W., Bernal P., Distrutti M., Goyeneche L., Bernal C. (2022) Going Beyond Normal: Challenges for Health and Healthcare in Latin America and the Caribbean Exposed by COID-10. Inter-American Development Bank Technical Note No IDB-TN-2471. Available at: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/viewer/Going-Beyond-Normal-Challenges-for-Health-and-Healthcare-in-Latin-America-and-the-Caribbean-Exposed-by-Covid-19.pdf (accessed 21 April 2023).

Schwalb A., Armyra E., Méndez-Aranda M., Ugarte-Gil C. (2022) COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean: Two Years of the Pandemic. Journal of Internal Medicine. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fjoim.13499

Segal P. (2022) On the Character and Causes of Inequality in Latin America. Development and Change, vol. 53, issue 5, pp. 1087–1102. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12728

United Nations (UN) Convention to Combat Desertification (2019) Latin America and the Caribbean Thematic Report: Sustainable Land Management and Climate Change Adaption. Available at: https://catalogue.unccd.int/1221_GLO_LAC_E.pdf (accessed 11 May 2023).

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (2018) China’s Role in Wildlife Trafficking and the Chinese Government’s Response. 6 December. Available at: https://www.uscc.gov/research/chinas-role-wildlife-trafficking-and-chinese-governments-response(accessed 21 April 2023).

World Bank (WB) (n.d.) World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed 12 May 2023).

World Bank (WB) (2022) Current Health Expenditure (% of GDP) – Latin America. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS?locations=ZJ (accessed 11 May 2023).

World Inequality Database (2020) Global Inequality Data – 2020 Update. Available at: https://wid.world/es/news-article/global-inequality-data-2020-update-3/ https://wid.world/document/inequality-in-latin-america-revisited-insights-from-distributional-national-accounts-world-inequality-lab-issue-brief-2020_09/ (accessed 11 May 2023).

Worldometer (n.d.) Latin America and the Caribbean Population. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/latin-america-and-the-caribbean-population/ (accessed 11 May 2023).

World Wildlife Federation (WWF) Inside the Amazon. Available at: https://wwf.panda.org/discover/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/amazon/about_the_amazon/? (accessed 11 May 2023).

Yang H., Simmons B. A., Ray R., Nolte C., Gopal S., Ma Y., Ma X., Gallagher K. P. (2021) Risks to Global Biodiversity and Indigenous Lands From China’s Overseas Development Finance. Nature Ecology & Evolution, vol. 5, pp. 1520–9. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-021-01541-w (accessed 11 May 2023).

Yeh K. B., Parekh F. K., Bogert B., Olinger G. G., Fair, J. M. (2021) Global Health Security Threats and Related Risks in Latin America: Global Security: Health, Science and Policy, vol. 6, issue 1, pp. 18–25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/23779497.2021.1917304.

Zalles V., Hansen M. C., Potapov P. V., Parker D., Stehman S. V., Pickens A, H., Parente L. L., Ferreira L. G., Song X.-P., Hernandex-Serna A., Kommareddy I. (2021) Rapid Expansion of Human Impact on Natural Land in South America Since 1985. Science Advances, vol. 7, no 14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abg1620.